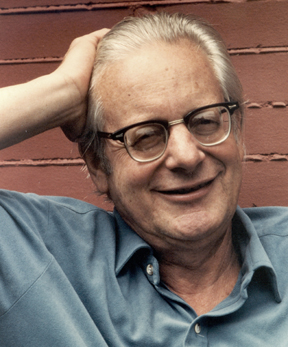

Leo Smit  Back to Program Main Page

Back to Program Main Page

Because the teaching of music is

communicated so intimately - the correcting of the hand position, the angle of the bow, the voice-leading of a counterpoint exercise – the biographies

of musicians often reveal through their pedagogical and early professional 'family trees' the personal links which propel the future's direction one way rather than another.

Leo Smit (1921-99) was the only child of Russian born parents and his musical precocity was recognized at an early

age. His father, at the time a violinist in the Philadelphia Orchestra, wanted him to be a piano virtuoso and studies at Curtis with José Iturbi augured such a

possibility. After the family moved to New York, three encounters however set in motion another idea of a life in music, that of a composer. At fourteen, Leo met Nicholas

Nabokov, composer and cousin of the writer Vladimir, who challenged him to compose a piece in one week's time. Leo dutifully wrote a binary sonata in the style of Scarlatti, which

after a brief glance, Nabokov dismissed. It was an original piece, something expressive of

Leo's experience he was looking for. Terrified but excited, Leo responded with a setting of the Yiddish poet Mani Lieb's Tzway

which elicited Nabokov's immediate delight and praise, an intoxicating, new experience for the young musician.

Although not a conventionally religious person, Leo composed pieces throughout his life which reflect his Jewish heritage. Tzadik (1984)

is the most substantial of these pieces but there is also a choral work for Sabbath services and a harmonization of Hatikvah, done in his last years. Leo thought highly of

Tzadik which he subtitled "Maker of miracles and wonders". It exists in three different instrumentations, for saxophone quartet, for string quartet and

piano trio. A tzadik is a spiritual master, one who acts righteously. The form of the piece alternates grave and somber ruminations, klezmer like dance music and cantorial melismas.

Just before the final section which evokes the shofar, Papageno and his flute enter, colored by intervals of the shtetl. At sixteen, without telling his parents, Leo auditioned for George Balanchine to be the rehearsal pianist for the world premiere of Stravinsky's new ballet,

Jeu de cartes. He got the job and soon found himself at the composer's side during the work's preparation. The

contact was electrifying, Stravinsky grunting and gesticulating the music's rhythms, often illustrating at the piano himself. At eighteen Leo gave his Carnegie Hall debut, which

included the first performance of a piece by Nabokov, and for a few years traveled the country as a Judson artist, but the die was cast – this kind of a career was not enough to

satisfy his sense of a life's work. Dance Card (1984?) acknowledges both the world of ballet and popular dance forms and is

full of musical allusions. In the opening Polka, for example, a tag from Gershwin's "How long

has this been going on?" appears in the trio. The Waltz is a meditation on intervals from

Wagner's Tristan and the Ragtime encodes B-A-C-H as a countersubject to the main strain. The referencing of other music is common in Leo's music, as it is in Stravinsky's, and is

present in all three of the pieces heard in this concert. The third decisive meeting of Leo's early career was in 1941 when he met Aaron Copland, whose newly composed

Piano Sonata Leo was the second to perform. Forty years later Leo would record the complete piano music of Copland for SONY, the definitive performances of

this music, at least in this writer's estimation. The link to Copland is reflected compositionally in Childe Emilie (1989), the first

of six song cycles on poems by Emily Dickinson. The over eighty songs which comprise the cycles, which are organized by

thematic groupings of the poems, are the summational work of the last ten years of Leo's life. While Copland's Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson are perhaps the best known song

cycle by an American composer and crystallized a certain declamation of the poet , Childe Emilie

finds its own world of evocation in music both straightforward and ecstatic. Leo often

said that his immersion in Dickinson's poems was the happiest period of his life creatively

and the sureness of these songs are reflected in the directness of their utterance, many of them written in a single sitting. As in Tzadik and Dance Card,

musical quotation is affectionately present. In the sixth song, 'Papa Above', the prayer from Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel is referenced in the piano accompaniment. This presence of the past, its living vitality, was the enduring lesson of Leo's teaching. When

he performed, he inhabited the music as though it were his own, finding it those composers he loved, especially Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Stravinsky and Copland the

compositional detail which in his view lent the work its uniqueness. When he discovered something, be it in music or literature, travel, science, whatever, his delight was infectious

and irresistable, as though he were the first to have made the discovery. It is characteristic

then that when he learned that the legendary Kansas City pianist Pete Johnson was living in obscurity in Buffalo in the early 60's, Leo who had known Pete's recording of

Zero Hour since the early 40's, sought him out and brought him to public attention again. In a letter,

written after a benefit concert for Pete, Pete gave Leo his most cherished review, "you were smokin' ". Leo's performance of Zero Hour

is of his note for note transcription of that 40's recording. Leo is buried in Forest Lawn, just a few hundred feet from Pete – a kind of compositional

detail in the life of this remarkable person. Nils Vigeland |